-BESTSELLING FREELANCE AUTHOR-

BERNARD HARE

BOOK REVIEWS

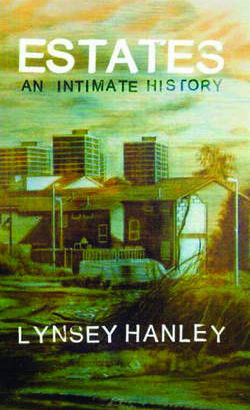

Estates - An Intimate History

By Lynsey Hanley

Literary Review, May 2007

As a boy growing up in inner city Leeds in the Sixties, I spent much of my spare time exploring what we called the ‘bomb sites’. In truth, few bombs were dropped on Leeds during the Second World War. The sites were, in fact, the result of the post war slum clearances. The people had gone, but the endless streets of trashed and dilapidated buildings remained. It was a dangerous place to play and we were lucky to survive, We were forever falling through floors and setting off incendiary devices,– but those old houses to us were a magnificent adventure playground.

We never asked where the people had gone. We never gave them a moment’s thought. Having read Estates, a remarkable debut by Lynsey Hanley, I now realise that the poor bastards had been shipped off to a life of purgatory in the back of beyond. They had been sent to places like ‘the Wood’ in Solihull, the biggest council estate in Europe when it was built at around the same time.

Hanley eloquently describes growing up on the estate. Isolated on the edge of town, with few shops, poor transport links and a depressing sameness to the houses, the place is an endless source of despair to her. ‘It'’s horrible, hostile, designed by a cyborg,’ she tells us. Throughout her adolescence, she longed to ‘escape’. I take issue with her slightly, as she almost presupposes that working class communities are places that must be escaped from. For those who remained in the inner cities, the working class values of community and solidarity did not begin to crumble until much later.

The book is an odd mix of memoir and English Social History. Probably against our wishes, we are next taken on a guided tour of the history of social housing policy from the Peabody Trust to the Public Finance Initiative. On occasion, the author only narrowly avoids morbid self-absorption, but her obsessive, quirky style adds colour and interest to what might otherwise be a dry subject.

The social housing movement began in the nineteenth century, with reformers like Sir Titus Salt taking the radical step of building decent homes for their workers, and continued in the first half of the twentieth century with the garden city movement and the new towns. Macmillan’'s ‘Great Housing Crusade’ in the fifties, however, turned out to be anything but, with jerry-built houses and high-rise ‘slums in the sky’ thrown up willy-nilly with little thought as to how poor environment affects the individual.

The affect, Hanley points out, is often insidious and alarming. She talks about the ‘wall in her head,’ which blighted her early life. She always knew there was another world, away from the council estate, but saw no way to reach it. Her horizons were limited by the general air of hopelessness, low expectations and depression which surrounded her. Isolated estates are often stigmatised by the better off and a slow, creeping self-doubt can overcome whole communities. Minds become closed when there is little to stimulate them.

Things changed irrevocably in the eighties with Mrs Thatcher’'s ‘Right to Buy’. In 1979, fifty percent of the population lived in rented social housing. Today, the figure is less than twenty percent. More and more of us own our own homes and the Right to Buy policy remains popular. Unfortunately, this leaves those without equity even more stigmatised and seeming even more like life's losers.

Hanley challenges our prejudices and overturns our stereotypes about ‘council scum’ tenants and ‘chavs’. This is an important book, which should be read by all self-respecting politicians, planners and architects. The affect of the Right to Buy has been to decimate the public housing stock and the government can’t, or won’t, put in the investment needed to regenerate our crumbling inner cities.

Reluctantly, Hanley agrees with New Labour that the only way forward is to accept private investment into the housing stock. Some land and stock will no doubt be handed over to property developers in return. One who dances with the devil must pay the piper, as it were. Reluctantly, I think she might be right.

Hanley gives the example of Broadwater Farm estate in London, where things were turned around with good planning, investment and community involvement. She concludes that while inequalities in health, wealth and opportunity exist, there will always be a need for social housing. We waste human resources if we stigmatise and exclude those who have to, or want to, take it up.

And if we get it wrong, we will end up with children playing on bomb sites all over again.

Ground Control - Fear & Happiness in the Twenty-First Century City

By Anna Minton

Literary Review, June 2009

A set of traffic lights near Leeds Bus Station breaks down with alarming regularity. It is a busy crossroads, with hundreds of cars passing every hour. Nevertheless, as a driver, it seems to me that the passage of traffic, if anything, speeds up when the lights are out. Drivers, who would normally robotically plough through green and slam the brakes on at red, suddenly wake up, slow down, look around and even allow pedestrians to cross before themselves traversing the junction. Other vehicles flash their lights, cede passage and behave as if road rage was a thing of the past. Despite hundreds of thousands of pounds worth of spending, the traffic flows just as well with no intervention. It is necessary to be able to cope with this kind of counter intuitive realisation before reading Ground Control: Fear & Happiness in the 21st Century City by Anna Minton, because much of what she says goes against accepted theory.

The central question of the book is why, despite increasing affluence, are we in Britain so anxious, stressed and depressed. Crime rates are dropping across the board but most people don't believe it, because the fear of crime is ever present and getting worse. Minton argues that the city itself is to blame for this paradox. The way the modern city is designed and run is simply not conducive to the peace of mind and well-being of its citizens. CCTV cameras, for example, follow our every move. This is supposed to make us feel secure, but somewhere at the back of our minds is the nagging doubt that all is not well. Minton argues that our anxiety is increasing largely because of two trends which have transformed our cities over recent decades. The growth of large scale development projects, like Canary Wharf, and alongside them the growth of gated communities to house the prosperous workers they produce.

Mrs Thatcher created the Urban Development Councils, chaired by property developers, ostensibly to counter inner city decay. Developers were handed large tracts of public land, protected from rates and taxes by enterprise zones and given complete freedom from planning laws. They created the shining glass towers and malls we know today. A clean and safe, if sterile, environment is created for shoppers, but security guards move on any unwanted stragglers from what is, after all, private property. It's great that the rotting inner cities I remember from my youth have been rebuilt, but I, like many others, just don't feel comfortable in these gleaming cathedrals of capitalism.

Alongside this, the growth of gated communities has led to increasing social disharmony. Those inside are frightened of those outside. Those outside are equally suspicious of the isolated oddballs inside. Studies have shown that open streets with an informal “eye” network have the lowest crime rates, yet the government encourages “defensible space” even in social housing. The very nature of these “executive ghettos” often only heightens the sense of isolation and anxiety. If anyone doesn't fit in, the solution, as always, is to exclude them. Feral youth are given ASBOs to keep them at bay, problem families are given parenting orders and the streets are swept clean at night with dispersal orders. ASBOs are handed out for minor offences, but when breached can result in a prison sentence. The effect is to criminalise swathes of the working class and to breed a subculture of crime in our midst.

Minton points out: These policies are damaging already low levels of trust between people and increasing the lack of trust in government and politicians, who, despite the tough-talking rhetoric, are unable to address the fear of rising crime. That is because their solutions are part of the problem.

Labour and Tories alike have followed the same long term policies and Minton challenges all of them. By the end of the book one is raging against politicians who promote simplistic solutions,– usually sourced in the USA,– to complex problems. We are left feeling that we have either been duped, or betrayed. In Europe, Minton points out, local government works with developers to find a balance between their needs and the needs of the city as a whole. Here, the public good seems to be what makes most money.

There is an alternative. European planning regulations encourage small shops and foster local culture, because smaller developments on a human scale chime better with the public and so have better chances to become successful places. Shopping isn't everything. Being able to walk around aimlessly, take in the sights and atmosphere and sit around doing nothing are equally important. Such an approach, Minton argues, offers us the opportunity to celebrate public life, culture and democracy, and to reinvigorate civic engagement in Britain. By moderating the architecture of extreme capitalism, we are much more likely to create happier, healthier and more diverse public spaces.